This site has been perserved as of Jim Dixon's passing in December 2016.

For questions or inquiries please visit allstarlink.org.

Welcome To Zapata

Telephony!

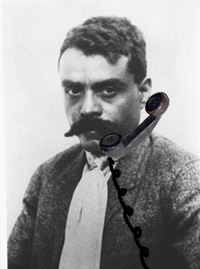

Gen. Emiliano Zapata, our

inspiration

Zapata Telephony, dedicated to bringing the world a much-needed reasonable and affordable Computer Telephony platform, and hence a revolution in the arena of Computer Telephony. Updated July 2009.

Click Here for the original (Ancient, circa 2002) Zapata Telephony Website

Click Here to see one thing I (Jim Dixon) have been working on for the past few years

About 25-30 or so years ago, AT&T started offering an API

(well, one to an extent, at least) allowing users to

customize functionality of their Audix voicemail/attendant

system which ran on an AT&T 3BX usually 3B10) Unix platform.

This system cost thousands of dollars a port, and had very

limited functionality.

In an attempt to make things more possible and attractive

(especially to those who didnt have an AT&T PBX or Central

Office switch to hook Audix up to) a couple of manufacturers

came out with a card that you could put in your PC, which ran

under MS-DOS, and answered one single POTS line (loopstart

FXO only). These were rather low quality, compared with

today's standards (not to mention the horrendously pessimal

environment in which they had to run), and still cost upwards

of $1000 each. Most of these cards ended up being really bad

sounding and flaky personal answering machines.

In 1985 or so, a couple of companies came out with

pretty-much decent 4 port cards, that cost about $1000 each

(wow, brought the cost down to $250 per port!). They worked

MUCH more reliably then their single port predecessors, and

actually sounded pretty decent, and you could actually put 6

or 8 of them in a fast 286 machine, so a 32 port system was

easy to attain. As a result the age of practical Computer

Telephony had begun.

As a consultant, I have been working heavily in the area of

Computer Telephony ever since it existed. I very quickly

became extremely well- versed in the hardware, software and

system design aspects of it. This was not difficult, since I

already had years of experience in non-computer based telephony.

After seeing my customers (who deployed the systems that I

designed, in VERY big ways) spending literally millions of

dollars every year (just one of my customers alone would

spend over $1M/year alone, not to mention several others that

came close) on high density Computer Telecom hardware.

It really tore me apart to see these people spending $5000 or

$10000 for a board that cost some manufacturer a few hundred

dollars to make. And furthermore, the software and drivers

would never work 100% properly. I think one of the many

reasons that I got a lot of work in this area, was that I

knew all the ways in which the stuff was broken, and knew how

to work around it (or not).

In any case, the cards had to be at least somewhat expensive,

because they had to contain a reasonable amount of processing

power (and not just conventional processing, DSP

functionality was necessary), because the PC's to which they

were attached just didnt have much processing power at that time.

Very early on, I knew that someday in some "perfect" future

out there over the horizon, it would be commonplace for

computers to handle all of the necessary processing

functionality internally, making the necessary external

hardware to connect up to telecom interfaces VERY inexpensive

and in some cases trivial.

Accordingly, I always sort of kept a corner of an eye out for

what the "Put on your seatbelts, youve never seen one this

fast before" processor throughput was becoming over time, and

in about the 486-66DX2 era, it looked like things were pretty

much progressing at a sort of fixed exponential rate. I knew,

especially after the Pentium processors came out, that the

time for internalization of Computer Telephony was going to

be soon, so I kept a much more watchful eye out.

I figured that if I was looking for this out there, there

*must* be others thinking the same thing, and doing something

about it. I looked, and searched and waited, and along about

the time of the PentiumIII-1000 (100 MHz Bus) I finally said,

"gosh these processors CLEARLY have to be able to handle this".

But to my dismay, no one had done anything about this. What I hadn't

realized was that my vision was 100% right on, I just didnt know

that *I* was going to be one that implemented it.

In order to prove my initial concept I dug out an old Mitel

MB89000C "ISDN Express Development" card (an ISA card that

had more or less one-of-everything telecom on it for the

purpose of designing with their telecom hardware) which

contained a couple of T-1 interfaces and a cross-point matrix

(Timeslot- Interchanger). This would give me physical access

from the PC's ISA bus to the data on the T-1 timeslots

(albeit not efficiently, as it was in 8 bit I/O and the TSI

chip required MUCHO wait states for access).

I wrote a driver for the kludge card (I had to make a couple

of mods to it) for FreeBSD (which was my OS of choice at the

time), and determined that I could actually reliably get 6

channels of I/O from the card. But, more importantly, the 6

channels of user-space processing (buffer movement, DTMF

decoding, etc), barely took any CPU time at all, thoroughly

proving that the 600MHZ PIII I had at the time could probably

process 50-75 ports if the BUS I/O didnt take too much of it.

As a result of the success (the 'mie' driver as I called it)

I went out and got stuff to wire wrap a new ISA card design

that made efficient use of (as it turns out all of) the ISA

bus in 16 bit mode with no wait states. I was successful in

getting 2 entire T-1's (48 channels) of data transferred over

the bus, and the PC was able to handle it without any problems.

So I had ISA cards made, and offered them for sale (I sold

about 50 of them) and put the full design (including board

photo plot files) on the Net for public consumption.

Since this concept was so revolutionary, and was certain to

make a lot of waves in the industry, I decided on the Mexican

revolutionary motif, and named the technology and

organization after the famous Mexican revolutionary Emiliano

Zapata. I decided to call the card the "tormenta" which, in Spanish,

means "storm", but contextually is usually used to imply a

"*BIG* storm", like a hurricane or such.

That's how Zapata Telephony started.

I wrote a complete driver for the Tormenta ISA card for *BSD,

and put it out on the Net. The response I got, with little

exception was "well that's great for BSD, but what do you

have for Linux?"

Personally, Id never even seen Linux run before. But, I can

take a hint, so I went down to the local store (Fry's in

Woodland Hills) and bought a copy of RedHat Linux 6.0 off the

shelf (I think 7.0 had JUST been released but was not

available on shelf yet). I loaded it into a PC, (including

full development stuff including Kernel sources). I poked

around in the driver sources until I found a VERY simple

driver that had all the basics, entry points, interfaces, etc

(I used the Video Spigot driver for the most part), and used

it to show me how to format (well at least to be functional)

a minimal Linux driver. So, I ported the BSD driver over to

Linux (actually wasnt *that* difficult, since most of the

general concepts are roughly the same). It didnt have

support for loadable kernel modules (heck what was that? in

BSD 3.X you have to re-compile the Kernel to change

configurations. The last system I used with loadable drivers

was VAX/VMS.) but it did function (after you re-compiled a

kernel with it included). Since my whole entire experience

with Linux consisted of installation and writing a kernel

module, I *knew* that it *had* to be just wrong, wrong,

wrong, full of bad, obnoxious, things, faux pauses, and

things that would curl even a happy Penguin's nose hairs.

With this in mind, I announced/released it on the Net, with

the full knowledge that some Linux Kernel dude would come

along, laugh, then barf, then laugh again, then take pity on

me and offer to re-format it into "proper Linuxness".

Within 48 hours of its posting I got an email from some dude

in Alabama (Mark Spencer), who offered to do exactly that.

Not only that he said that he had something that would be

perfect for this whole thing (Asterisk).

At the time, Asterisk was a functional concept, but had no

real way of becoming a practical useful thing, since it

didnt, at that time, have a concept of being able to talk

directly (or very well indirectly for that matter, being that

there wasnt much, if any, in the way of practical VOIP

hardware available) to any Telecom hardware (phones, lines,

etc). Its marriage with the Zapata Telephony system concept

and hardware/driver/ library design and interface allowed it

to grow to be a real switch, that could talk to real

telephones, lines, etc.

Additionally Mark has nothing short of brilliant insight into

VOIP, networking, system internals, etc., and at the

beginning of all this had a great interest in Telephones and

Telephony. But he had limited experience in Telephone

systems, and how they work, particularly in the area of

telecom hardware interfaces. From the beginning I was and

always have been there, to help him in these areas, both

providing information, and implementing code in both the

drivers and the switch for various things related to this.

We, and now more recently others have made a good team (heck

I ask him stuff about kernels, VOIP, and other really

esoteric Linux stuff all the time), working for the common

goal of bringing the ultimate in Telecom technology to the

public at a realistic and affordable price.

Since the ISA card, I designed the "Tormenta 2 PCI Quad

T1/E1" card, which Mark marketed as the Digium T400P and

E400P, and others have and still are as different part numbers, also). All of the design files (including photo plot files) are

available on the this website for public consumption.

As anyone can see, with Mark's dedicated work (and a lot of

Mine and other people's) on the Zapata Telephony drivers (now called "DAHDI") and the Asterisk

software, the technologies have come a long, long way, and

continue to grow and improve every day.

"We don't need no stinkin' DSP!!"

Zapata Technology -- Design Philosophy

The Zapata Technology is based upon the concept that computer hardware is now fast enough to handle all processing for computer telephony applications, including that which was traditionally limited to DSP's and embedded controllers.

DSP's are optimized for signal processing applications and functions, and do so far more efficiently then traditional general-purpose processors, such as those found in PC's and standard computer systems. Despite their serious advantage in these types of applications, they have many logistical deficiencies that often make their use far out of reach of the common mortal. These deficiencies include entirely proprietary architectures, both hardware and software, requiring specialized knowledge and experience, not to mention extremely specialized (and way way expensive) development hardware and software. As a result, the use of DSP's has become limited to environments where the extreme expense of the requirements of their use (both development environment and personnel/expertise, and in some cases the DSP parts themselves) can be recovered.

Unfortunately, what this also does, is completely discourage the open-source concept in any of these technologies, since it would be impossible to recover high costs, and even if source code for DSP's was made available,very few could afford the equipment necessary to develop it.

The Zapata Technology is an attempt to address these issues. Even the simplest personal computers are quite fast these days. Even if DSP-style processing is only possible in an inefficient manner (on this type of architecture), and bus-I/O is HORRIBLY SLOW (for example, on a 48 port system with the Tormenta ISA card, a 550Mhz Pentuim-III system spends OVER 1/3 of its time halted, waiting for bus-I/O to complete), there still is plenty of time for applications to run and operate in a reasonable manner. Certainly it is a horrible waste of processor time, but it would certainly appear the the serious advantages of this approach outweigh the wastes. Besides, processors are getting faster all the time. As a result, the waste and inherent architectural inefficiencies will become less of an issue over time. In addition, a PCI version of the card helps this a great deal.

The truly beautiful part of this technology is that since all processing takes place within the main CPU(s), there is absolutely minimal hardware necessary (just enough to make the T-1 data accessible via the bus), keeping costs to an absolutely unprecedented minimum (various commercial solutions list at about $10,000.00 US, give or take a couple thousand. The Tormenta ISA card used to cost $275.00 US when we were selling it directly). In addition, it allows all development issues to be put in the hands of literally anyone inclined to do so. It requires no specialized development environment or knowledge, being merely yet another driver and library, just like all the ones for other types of hardware. The Tormenta ISA card contained entirely off-the-shelf available parts, none of which require programming, thus allowing for construction by anyone (you didn't have to buy it from us, or anyone else).

Where we are now

Zapata Technology has now been used by and included in a number of software

packages and a number of companies now produce Zapata Technology-Compatible

hardware. It has indeed started a revolution in telephony technology

and the telephony business model.

We have made a significant contribution in the area of entirely changing the face and direction of telephony,

and have very much succeeded in making reasonable telephony at reasonable

price available to all people, everywhere.

It's very encouraging to see that this project has met with such sucess

in the last 10 years or so, and we can only hope for much more use and

improvements in the years to come.

"¡Viva Zapata!"

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to thank the following

people for their

gracious contributions to this project, or whose work has greatly

contributed to this

technology: David Kramer, Todd Lesser, Jim

Gottlieb, Steve RoDgers, Joe

Talbot, John Higdon, Clint Kennedy, Steve Thomas, Steve Underwood, Tony Fisher (may he

rest in peace),

Jesus Arias, Mark Balliet, Christian Mock, Christopher Lee Fraley,

Julius Smith, Joe

Campbell, the unknown person who wrote the ADPCM converter routines,

and of course, Mark Spencer and Digium. And Let us not forget to properly acknowledge the help of Linus Torvalds

for bringing us Linux, and providing us with such helpful encouragement

such as: With the exception of items protected by the

GNU General Public

License (which are clearly indicated as such), the technologies,

software, hardware,

designs, drawings, schematics, board layouts and/or artwork, concepts,

methodologies

(including the use of all of these, and that which is derived from the

use of all of

these), all other intellectual properties contained herein, and all

intellectual property

rights have been and shall continue to be expressly for the benefit of

all mankind, and

are perpetually placed in the public domain, and may be used, copied,

and/or modified by

anyone, in any manner, for any legal purpose, without restriction. The text and non-informational images of this

website (not

the information contained herein) is Copyright © 2000-2009 Zapata

Telephony. May be reproduced

in full, or in part, in any manner without modification.

History of Zapata Telephony and how it relates to Asterisk PBX

By Jim Dixon, WB6NIL <jim@lambdatel.com>

"Hmm.. Sounds like somebody has designed a truly crappy card. Everything

is allowable in the name of being cheap, I guess ;)"

-- Linus Torvalds, Feb 5 2001

See original post on Linux Kernel Mailing List